Termite & Pest Control Service

Taking ACTION against pests since 1969

Termite and Pest Control Services

Taking ACTION against pests since 1969

ExcellentBased on 3531 reviews

Calvin BoveeDecember 21, 2023Used Action Termite & Pest Control to treat my termites. They were extremely knowledgeable, professional, and responsive throughout the process. Art & Roy were both a pleasure to work with. Highly recommend!

Calvin BoveeDecember 21, 2023Used Action Termite & Pest Control to treat my termites. They were extremely knowledgeable, professional, and responsive throughout the process. Art & Roy were both a pleasure to work with. Highly recommend! Shelle HarmanDecember 21, 2023Daniel was the best finding the issue and teaching me! Thank you !!

Shelle HarmanDecember 21, 2023Daniel was the best finding the issue and teaching me! Thank you !! Denise WhismanDecember 21, 2023Bill was awesome to work with. Incredibly knowledgeable and patient while explaining everything. Can't thank Bill enough for his quick work and professionalism!

Denise WhismanDecember 21, 2023Bill was awesome to work with. Incredibly knowledgeable and patient while explaining everything. Can't thank Bill enough for his quick work and professionalism! Bob DonleyDecember 21, 2023Very professional and arrived on time.

Bob DonleyDecember 21, 2023Very professional and arrived on time. John LuciusDecember 20, 2023Knowledgeable, insightful courteous, listens to concerns and resolves them..

John LuciusDecember 20, 2023Knowledgeable, insightful courteous, listens to concerns and resolves them.. Raquel AmadorDecember 20, 2023Mike Boswell got everything taken care of and answered all my questions/doubts.

Raquel AmadorDecember 20, 2023Mike Boswell got everything taken care of and answered all my questions/doubts. Lisa TreatDecember 20, 2023Battle with the bugs begins! Excellent advice and service. Thanks!

Lisa TreatDecember 20, 2023Battle with the bugs begins! Excellent advice and service. Thanks!

What our customers are saying...

What sets us apart...

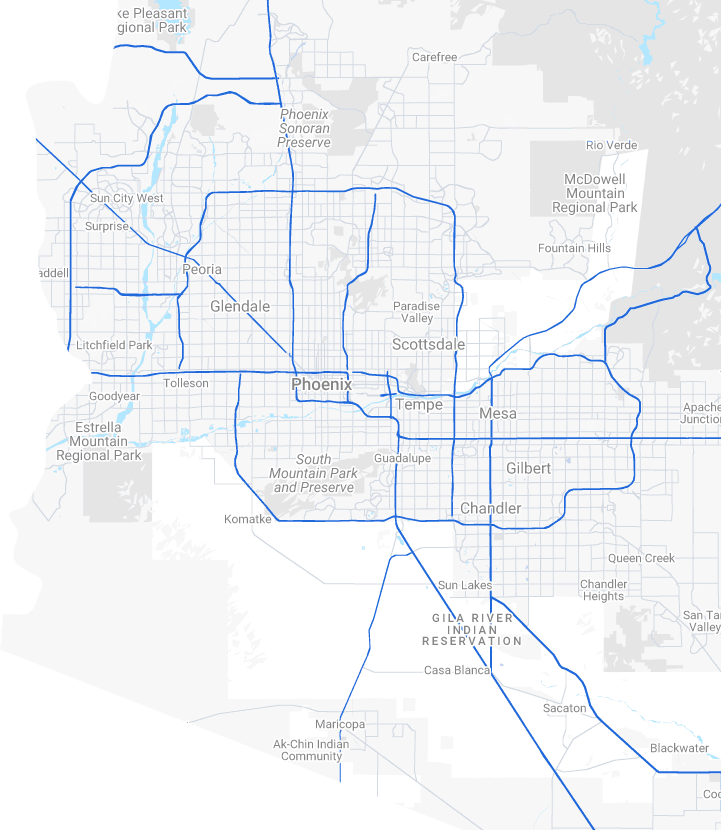

Pest Control Phoenix AZ Trusts

We are a family owned & operated pest control company located in Phoenix, AZ. Serving Arizona since 1969, we have built a reputation for delivering the highest level of client service in the industry and have an all-star team of pest industry professionals that provide thousands of treatments each year. Our team of experts provide both residential and commercial services across the entire Valley. From recurring pest services that treat over 50 types of insects to industry leading termite treatment solutions, you can count on us to provide a solution that is safe, effective, and tailored to your specific pest control needs.

Our Pest Services

#1 provider of termite treatments in Phoenix AZ

Pest Control Company Homeowners & Commercial Businesses Trust

Pest Control Phoenix Rated 5 Stars with Over 5,000 Reviews!

Are pests bugging you? If you’re searching for “pest control Phoenix”, “termite control Phoenix” “pest control near me” or “termite control, inspection, or treatment near me.”

Look no further, our experts at ACTION Termite & Pest Control can help you with both, there’s no need to separate companies.

Experience with all types of bugs, termites, pests, for commercial and home pest control

We have experience with all types of common pests, provide the best pest control and termite treatment in the Phoenix area and have an initial service that is very thorough and checks all areas of your home or business. Our family owned, highly trained, professional exterminators provide free inspections and a free estimate on all home pest control and commercial pest control. From Sun City to Union Hills and Indian School Rd Scottsdale AZ, New River, Litchfield Park, Cave Creek and all surrounding areas we provide the best response time to your pest control needs. We have over 50 years experience.

Top Rated & Reviewed Pest Control

Our Family Owned Pest Control Company is one of the top rated and reviewed local pest control companies in the Phoenix, AZ metro area with well Over 5,000, 5 Star Reviews. We can handle all types of urban, rural, and desert pest control services. Many pest control companies don’t offer bed bugs, scorpion issues, carpenter ants services like we do as well as reliable pest control you can count on each month. If you have a pest problem contact our Phoenix Arizona termite specialists.

Strong 50 Year+ Reputation of Pest & Termite Control Services

ACTION Termite & Pest Control company is proud of its reputation for consistently maintaining the highest standards in the home pest control service & commercial pest control service for commercial properties we provide, products we use, our expertise in the elements of termite and home pest control. We encourage new customers to verify our excellent standing with the Arizona Office of Pest Management (OPM) and the Better Business Bureau to see we haven been doing this for a lot more than just a few years. We don’t have an average rating we have Great Reviews when it comes to complete pest management book an initial service today.

Licensed Pest Control Technicians

Our licensed technicians are involved in ongoing training programs to ensure that our customers in the Phoenix AZ area receive, not only excellent service but the latest and best technology available for the identification and solution of any pest including bed bugs.. We pride ourselves in being one of the BEST family owned pest control companies in Phoenix AZ providing top rated Phoenix pest control services, response time, and we are not just the regular bug guy. We get rid of your pest problem, sign up for an initial service. Call us for a free quote or submit your name, phone, and email address via our contact form. We pest control services for the entire Phoenix, AZ metro Valley Wide area.

Pest Control in Phoenix AZ Metro area

Taking ACTION against pest since 1969, (Over 50 years Experience) with Pest & Termite Control Experience. Over 5,000 5 Star Reviews!

The cost of pest control in Phoenix can vary based on several factors like the type of pest, your home’s size, and the infestation’s severity. Here’s a general breakdown:

One-time treatment: Expect to pay around $100-$250 for a single treatment against common pests like ants or spiders.

Monthly service: If you encounter a more troublesome infestation or want preventative measures, a monthly service costing roughly $50-$75 might be suitable.

Termite treatment: Termites require specialized treatment, which can be pricier, ranging from $500-$1,000 or more.

Here are some additional factors that can influence the cost:

Home size: Bigger homes naturally cost more to treat.

Infestation severity: Extensive infestations typically require more resources and therefore have higher costs.

Pest control method: Techniques like heat treatment tend to be more expensive than others.

Chosen company: Different pest control companies will have varying price structures. Comparing quotes from a few before deciding is always wise. You can Schedule with us directly online and see our pricing at anytime here

The cost of pest control in Phoenix can vary based on several factors like the type of pest, your home’s size, and the infestation’s severity. Here’s a general breakdown:

One-time treatment: Expect to pay around $100-$250 for a single treatment against common pests like ants or spiders.

Monthly service: If you encounter a more troublesome infestation or want preventative measures, a monthly service costing roughly $50-$75 might be suitable.

Termite treatment: Termites require specialized treatment, which can be pricier, ranging from $500-$1,000 or more.

Here are some additional factors that can influence the cost:

Home size: Bigger homes naturally cost more to treat.

Infestation severity: Extensive infestations typically require more resources and therefore have higher costs.

Pest control method: Techniques like heat treatment tend to be more expensive than others.

Chosen company: Different pest control companies will have varying price structures. Comparing quotes from a few before deciding is always wise. You can Schedule with us directly online and see our pricing at anytime here

There’s no single “hardest” household pest as different factors contribute to the difficulty of eradication. However, three contenders frequently top the list:

1. Termites: These tiny wood-munchers work silently, causing hidden damage that can be costly to repair. Their cryptic nature within walls and foundations makes detection and treatment challenging. Additionally, some species exhibit resistance to common pesticides, requiring specialized protocols.

2. Bed Bugs: These nocturnal bloodsuckers excel at hiding in tiny crevices and seams, making comprehensive extermination difficult. Their rapid reproduction, ability to survive for months without feeding, and potential resistance to insecticides further complicate matters. Professional treatment often involves multiple applications and meticulous inspection to ensure eradication.

3. Cockroaches: Though seemingly easy to squish on sight, cockroaches pose a formidable challenge due to their adaptability and resilience. They breed quickly, hide in almost any nook or cranny, and can even survive short-term exposure to some insecticides. Addressing underlying factors like sanitation and moisture control alongside insecticide use is crucial for successful cockroach control.

Ultimately, the difficulty of eradicating any pest depends on its biology, habits, the extent of the infestation, and the choice of control methods. If you suspect a pest problem, seeking professional help from a qualified pest control company is generally advisable. They can assess the situation, recommend the most effective approach, and implement a targeted treatment plan to tackle the issue effectively.

There are several reasons why pest control can seem expensive, and the cost can vary depending on the specific situation. Here are some key factors contributing to the price:

Expertise and Licensing: Pest control professionals require specialized training and licensing to ensure safe and effective pest elimination. This involves knowledge of pest biology, control methods, safety protocols, and regulations. The cost of maintaining this expertise and licenses is reflected in their service fees.

Cost of Services and Materials: Effective pest control often involves a combination of techniques and materials. This might include insecticides, baits, traps, monitoring devices, specialized equipment, and protective gear. The cost of these tools and materials adds up, especially for more complex treatments like heat or fumigation.

Time and Labor: Treating pests effectively often takes time and effort. Technicians might need to conduct thorough inspections, apply multiple treatments over several weeks, and follow up to ensure the infestation is eradicated. This labor cost contributes to the overall service price.

Severity of Infestation: Larger or more established infestations require more extensive and intensive treatments compared to catching a problem early. This might involve multiple visits, stronger chemicals, or additional techniques, driving up the cost.

Type of Pest: Different pests require different approaches and strategies. Some, like termites or bed bugs, have complex life cycles and require specialized methods, raising the cost compared to dealing with simpler creatures like ants or spiders.

Preventative vs. Reactive: Proactive pest control services generally have a lower ongoing cost than dealing with established infestations. Regular inspections and preventative measures can nip smaller problems in the bud before they escalate, often saving money in the long run.

Company Overhead: Like any business, pest control companies have overhead costs like transportation, office space, insurance, and employee salaries. These expenses are factored into their pricing structure.

While pest control can seem expensive upfront, it’s important to consider the potential cost of neglecting the problem. Untreated infestations can cause damage to your property, pose health risks, and be more challenging and expensive to eradicate later. Weighing the potential long-term costs against the upfront investment in professional pest control can help you make an informed decision.

Remember, comparing quotes from different companies and discussing your specific pest problem can help you find the most cost-effective solution for your situation.

The frequency of pest control in Arizona depends on several factors, including:

Climate: Arizona’s warm climate allows many pests to thrive year-round, with peak activity in spring and summer. This generally necessitates more frequent treatment compared to colder climates.

Location: Pest populations and species vary across Arizona. Areas with more vegetation or proximity to water sources might require more frequent treatment than drier, urban areas.

Type of pest: Different pests have different lifecycles and activity patterns. Scorpions and spiders might warrant monthly or bi-monthly treatment, while ants and roaches might be manageable with quarterly services.

Severity of infestation: Large or established infestations will require more frequent treatments compared to catching a problem early.

Personal preference: Some homeowners prefer preventative measures and opt for regular pest control services, while others only call for help when they see an active infestation.

Here’s a general guideline:

- Bi-monthly (every other month): This is a common choice for many Arizonans, offering good protection against common pests like scorpions, ants, and roaches.

- Monthly: Recommended for severe infestations, homes with high pest pressure, or those seeking maximum protection against specific pests like scorpions.

- Quarterly: Can be sufficient for some homes with minimal pest activity and less concern about specific dangers like scorpions. However, this offers less preventative protection and leaves you more vulnerable to potential infestations.

Remember, these are just general recommendations. It’s best to consult with a reputable pest control professional at ACTION Termite & Pest Control to assess your specific needs and recommend the most effective and cost-effective frequency for your situation. We can tailor a treatment plan based on your pest concern, location, and preferences.

Whether pest control is worth it hinges on specific factors like the infestation’s severity, the pest type, and your budget.

Reasons for professional pest control:

- Effectiveness: Professionals wield powerful, consumer-unavailable pesticides and possess the expertise to utilize them safely and effectively. DIY methods may prove insufficient.

- Time and money savings: DIY attempts can involve wasted time and funds on ineffective solutions. Professionals tackle the problem swiftly and efficiently.

- Health and property protection: Certain pests like termites and mosquitoes pose health risks, while others like rodents can damage property. Pest control safeguards against these dangers.

However, consider these before opting for professionals:

- Minor infestations: A handful of pests might be manageable through DIY methods.

- Budget constraints: Professional services can be costly. DIY might be an initial option for budget-conscious individuals.

- Pesticide concerns: Some individuals prioritize eco-friendly methods and might be hesitant about using pesticides. Talk to a pest control company about eco-friendly options if this is a concern.

Ultimately, the decision rests with you. Weigh the pros and cons carefully before choosing the best approach for your situation.

Remember, choosing a reputable company like ACTION Termite & Pest Control is crucial if you opt for professional services. Seek recommendations, read reviews, and compare quotes from different companies before making a decision. Ensure you understand the service details, including the number of treatments and warranty specifics.